Lesson 4: Finding Information Resources

Learning Objectives

- Locate library materials using the library catalog

- Recognize and locate eight types of information available from the library

- Understand how different types of information support student research

Estimated time to complete: 60 minutes.

Searching the Library Catalog

The online library catalog, indexes materials physically located on the library shelves or behind the circulation desk. Some items in the catalog can be accessed online such as eBooks.:

- Print, electronic, and audio books

- Videos and DVDs

- Government documents

- Periodicals

- Computer software

- Special collections

The library catalog does provide

- Detailed information on all items owned by a library (e.g., author, title, publisher information)

- Information on how to access an item (e.g., call number, or Web link for online access.)

The library catalog does not provide

- Individual articles within journals, magazines, or newspapers

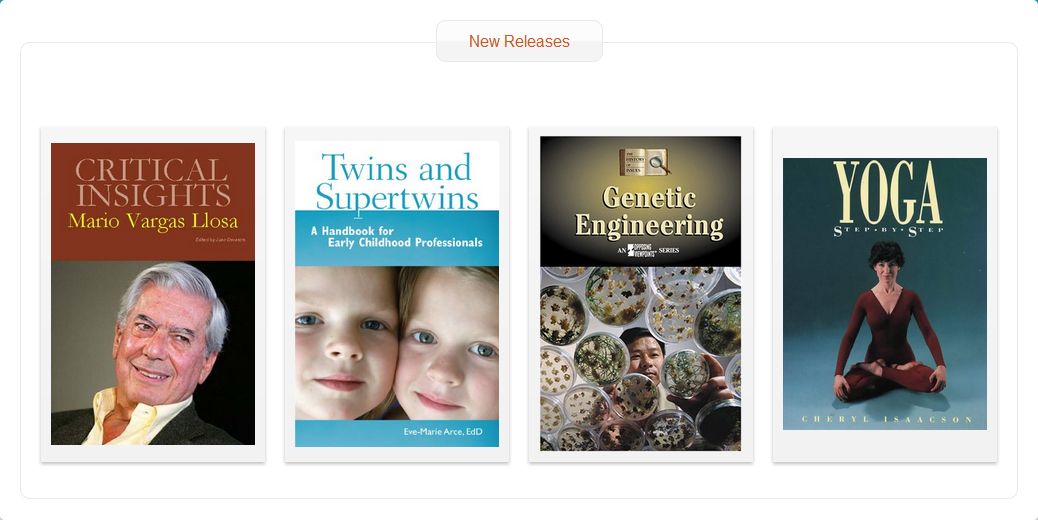

Basic Search

The Basic Search has a single search box, as illustrated below.

The default search will scan the entire bibliographic record to find the words you enter. In the library catalog, type in your term and clisk “Search.”

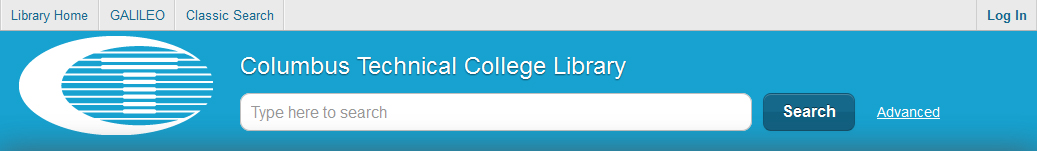

New Releases

Directly below the basic search bar are rotating covers of our newest titles. Simply click on a cover to view the item in question.

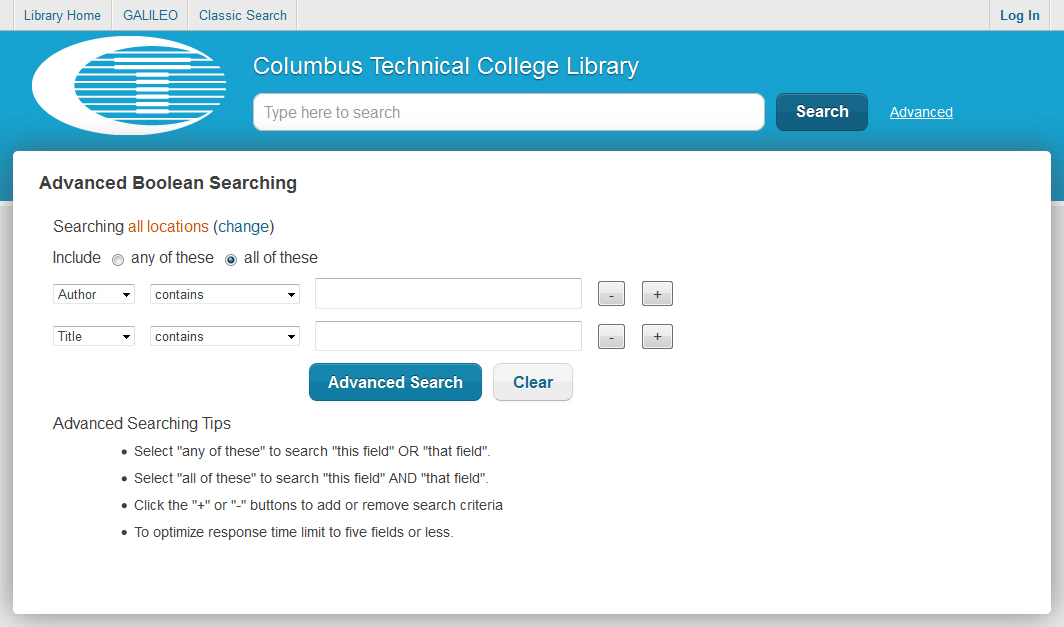

Advanced Search

Advanced Searches are built on drop down boxes that let you search specific fields as well as the ability to eliminate search terms. The areas you can search include Any Field, Title, Author, Series, Subject, Note, Tag, ISBN, and UPC. To eliminate a term, select “does not contain” in the second drop down menu. You can also combine searches for similar terms by selecting “any of these” to search “this field” OR “that field”.

Combining search terms can help with finding a specific resources needed. Using a subject guarantees that the main topic of the book will a focus. Try using similar terms if you are not getting the results you want.

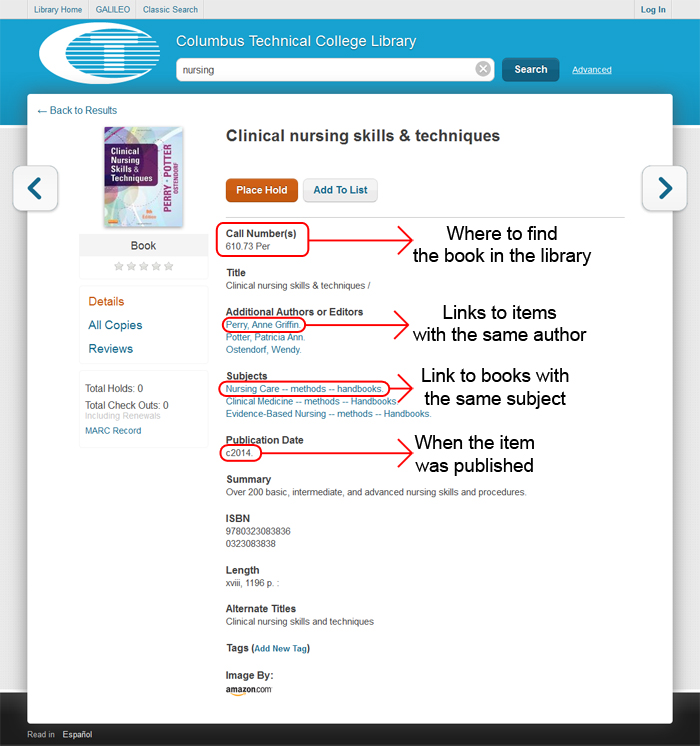

Bibliographic Record

What is a bibliographic record? It is the detailed information about an item presented in the library catalog. This example of a bibliographic record is for a book called Ecological Integrity by David Pimentel. It shows a picture of the book and links to book reviews, a summary, other titles by David Pimentel, other library materials on the subject of ecological integrity, and the call number to locate the book on the shelf.

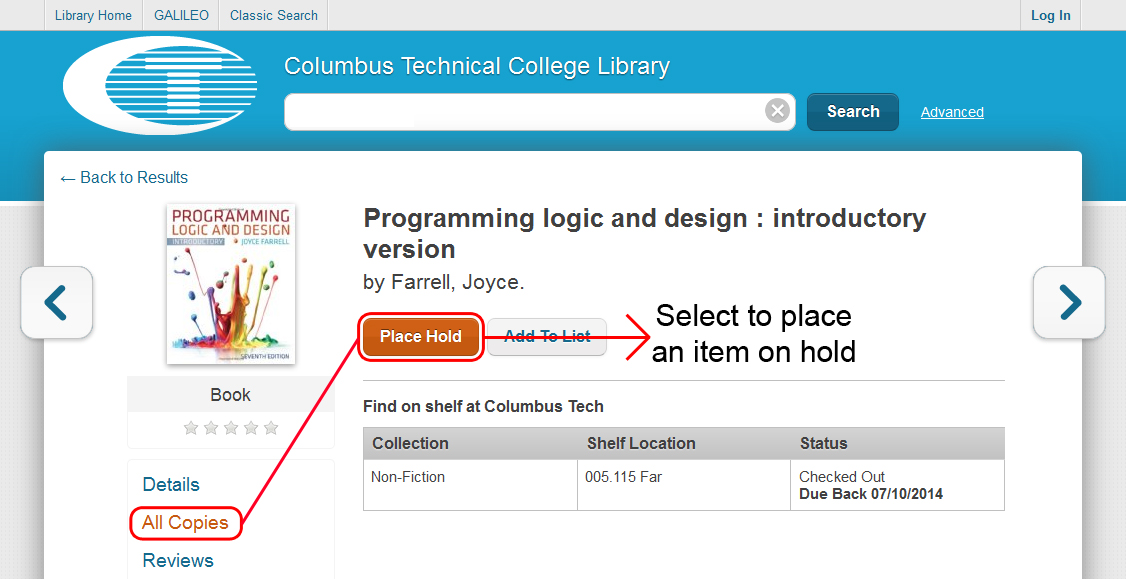

Request an Item

An item’s availability is automatically displayed in the Search Results. It will say Not Available in All Locations. Click on the Place Hold button to reserve the item once it is returned to the library.

You can also check in the item record by clicking the All Copies link on the left hand side. Click the Place Hold button to request the item.

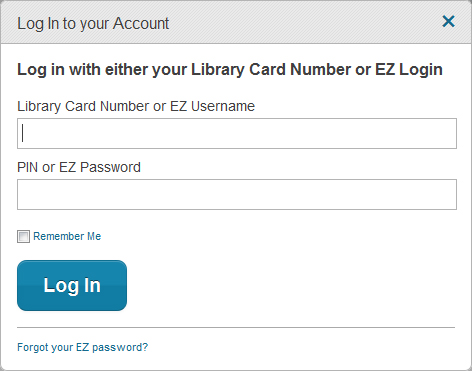

When you try to place a hold on an item, you will be asked to log in with your Library Card Number or EZ Username. The default library card number is actually your student id number. Your default pin is the last four of your student id number.

If you are having trouble logging into your account, come to the library circulation desk. We can help you set up or adjust your account.

Call Numbers

Call numbers are labeled on the spine of library materials and determine how those materials are organized. Call numbers in the library range from 000 to 999 and are based on the Dewey Decimal system. Numbers are arranged in ascending order. These numbers are typically followed by three letters, either the author’s last name or the editor’s last name. More information about the Dewey system is below.

Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC)

Some of the following information is from ipl2 and is used with permission.

The Dewey Decimal Classification system (DDC) is the world’s most widely used library classification system. It was created by Melvil Dewey in 1876 with aims to “organize all knowledge.” The Dewey Decimal Classification call numbers are numeric “addresses” that group library materials by a main subject, also referred to as a class. Since each class is assigned a number, call numbers for books in a given class will always begin with that number in the 100’s section starting at 001. Subjects fall into 10 main classes, 100 divisions, and 1000 sections creating a three-digit number that can be expanded with an unlimited number of decimal places to capture additional details about the item. As an example, the call number for a book in social sciences starts with 300. Consult OCLC‘s website for additional information. There is also a PDF guide and a PowerPoint presentation.

In the table below is a more in depth dissection of a call number.

| Decoding Dewey Decimal Call Numbers. Example: 822.33 Sha | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main Class | 800 | Literature |

| Division | 820 | English Literature and Rhetoric |

| Section | 822 | English Drama |

| 822.3 | Drama of Elizabethan period, 1558-1625 | |

| 822.33 | The works of William Shakespeare | |

| 822.33 Sha | Cutter Number identifying author or editor’s last name. |

Dewey Classification numbers (DDC) is a proprietary system, currently published by the Online Computer Library Center, Inc. (OCLC).

Take a look at this YouTube video, by Howcast about the Dewey system (2:03):

Summary: Video goes over the Dewey Decimal System

Basic Information: Encyclopedias and Dictionaries

If you are not familiar with a research topic, encyclopedias are a good place to start. Encyclopedia articles are written by subject specialists in the field and generally provide comprehensive overviews and background information. They also include selective bibliographies of other authoritative books and articles on the subject being researched.A general encyclopedia is often the best place to start research because it contains information on almost every subject. Specialized encyclopedias are focused on specific subject fields.

Examples of general encyclopedias:

- Encyclopaedia Britannica

- World Book Encyclopedia

Examples of specialized encyclopedias:

- Encyclopedia of Criminology and Deviant Behavior

- McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology

- The Oxford Companion to American Literature

- The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

Search Strategy for Locating Encyclopedias

Encyclopedia’s are typically located in the REF section of the library. You can locate encyclopedias by searching the library catalog. Not every encyclopedia actually uses the word encyclopedia or encyclopedia in the title, for example, The Oxford Companion to English Literature or The Library Of Literary Criticism.

- For the basic search box, enter in encyclopedia as that is the more common spelling found in our collection. You can also add an additional word for a particular subject, such as literature.

- In the Advanced Boolean Searching, select Include any of these, select Title contains for two search boxes. Enter in encyclopaedia for one box and encyclopedia for the other box.

- Typing the word dictionar* and your subject term to find reference titles that define terms.

You can also do a subject search on the general term for your topic and see what the call number is. For example, a subject search for “chemistry” identifies the call number 540. You can go to that area of the reference collection and browse for chemistry background sources.

Is Wikipedia a good source for background information? Watch this video to find out more.

Basic Information: Periodicals

Periodicals are materials that are published at regular intervals (monthly, quarterly, daily, etc.). There are four types:

- Scholarly journals

- Trade journals

- Magazines

- Newspapers

Periodical articles contain current information, which is especially important in fields such as science, business, psychology, and technology. Also, subjects which are too new or too specialized to be covered by books are often covered by magazines, journals, and newspapers. Instructors often ask that students use “scholarly articles” in their research. What does that mean?

Scholarly v. Popular Articles

Scholarly articles can also be referred to as peer-reviewed, refereed, academic, or research articles. It is often difficult, especially when using online databases or the Internet, to recognize and decide whether an article is “scholarly.” Generally, a scholarly article is a lengthy report on original research or experimentation, and contains data illustrated by graphs, charts, or diagrams. Scholarly articles usually follow the same structure:

- Abstract or summary

- Problem statement

- Methodology and discussion

- Conclusion

- List of cited references

Often written by experts and published by a professional organization or university, a scholarly article is reviewed by a group of the author’s peers before it is published. If the article is not approved, it is not published. This process of peer review ensures better quality research for students to use. Anatomy of a Scholarly Article (N.C. State University Libraries) offers clues to help you identify parts of a typical scholarly article.

The chart below provides general guidance on the differences between the four types of periodicals:

| Scholarly Journal | Trade Journal | Magazine | Newspaper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article Length | Long | Short | Short | Short |

| Who is the Author? | Academic scholars and researchers | Professionals in the field and journalists with subject expertise | Journalists and freelance writers | Journalists |

| References Available? | Long list of references for most articles | Some articles have a few references | Sources might be partly identified in the article | Sources might be partly identified in the article |

| Graphics | Graphs, charts and tables Few or no colors Ads are very rare | Photographs Graphs, charts and tables Trade-related ads | Many photos and other graphics Lots of colors Lots of ads, including full-page ads | Photos and other graphics in black and white Lots of ads; some full-page |

| Publisher | Professional societies University and scholarly presses Research institutes | Professional society or trade group Commercial publisher | Commercial publisher | Commercial publisher |

| What’s the Value? | Published research results that can be cited to back up an argument | Recent news in a particular field Book reviews | Short news articles on current events Interviews with political leaders, etc. | Latest news on a topic Local papers are useful for local issues |

| Examples | Journal of Criminal Law American Journal of Clinical Nutrition | Library Journal Today’s Chemist at Work Science | Newsweek Time PEOPLE Sports Illustrated Fortune | The New York Times The Washington Post The Wall Street Journal |

Based on a table by Gail Gradowski, Designs for Active Learning. Chicago American Library Association, 1998. p. 15.

Finding Periodical Articles on Your Topic

There are many different ways to find articles for an assignment. These are three suggestions to help you get started.

1. Look in the bibliography of a book, or the list of cited references for an article.

If you already have a good book or article on your topic, the easiest way to find more is to look in the bibliography or cited references. It can be difficult to determine the type of source in a citation. To help distinguish between citations for books and periodicals, remember that periodical citations will have volume and / or issue numbers.See Lesson 7: Citing Sources and Fair Use for more information on interpreting citations.

2. Look in a library database that covers your topic.

Library databases generally provide citation information and a brief summary for the periodical articles they index. Many of your library’s databases provide the full text (entire article) of most of the articles they contain, and allow you to save, print, and e-mail the article. Other databases contain only the citations and/or abstracts. Some databases cover one subject, and other databases are general-purpose and cover many subject areas.

- To locate a database by subject, check the list of databases organized by subject coverage.

- EBSCOHost’s Academic Search Complete is a good general-purpose database to start researching.

- See Lesson 3: Searching Library Databases for more information.

3. Search for periodical titles that cover your topic.

If you prefer, you can browse through entire issues of a newspaper, magazine, or journal. If your library does not have access to a particular periodical title or to the full text of an article, you may be able to request a copy through interlibrary loan. Ask a librarian for information.

- Use the e-journal finder to find out if a specific magazine or journal is available online. Search for electronic journals and magazines by title.

- To find out if the library subscribes to the print version of a specific periodical title, browse the library Periodicals page online.

Primary and Secondary Sources

It is important to understand the distinction between primary and secondary sources when you are researching a topic, particularly if your professor requires a certain number of primary sources to be included in your research.

Primary Sources

A primary source is an account by an eyewitness or the first person to record an event. Examples are:

- Diaries, letters, minutes of meetings, news footage, newspaper articles.

- Data obtained through original research, statistical compilations or legal requirements such as reports of scientific experiments, U.S. census records, and public records.

- Creative works such as poems, plays, short stories, novels, musical pieces, or artwork.

- Artifacts such as stone points, pottery, furniture, and buildings.

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources are works that interpret the primary data. Examples are:

- Books about historical events or people, such as the biography John Adams by David McCullough.

- Journal articles about the role of tobacco in colonial economy.

- Critical reviews of poems, plays, short stories, novels, musical pieces, or artwork.

If you have questions regarding whether or not an item you are viewing is a primary or secondary source, ask a librarian.

Biographical Information

A biography is an account of the basic, special and important events in a person’s life. There will be many times during your years in college and later in life that you will need to find biographical information about a person. Biographical sources cover living and deceased persons, notable persons of a particular nationality, persons in specific occupations, celebrities, and civil and government leaders.

Types of Biographical Resources

Biographical information is found in a variety of formats: full-length books, entries in collected works such as encyclopedias and biographical dictionaries, or periodical articles. Biographies may be brief and cover only basic information about a person’s life such as dates of birth and death, education and vocation. A biography may also be very detailed, and cover the cultural background, accomplishments, and historical significance of an individual.

- Primary biographical sources are sources written by the person you are researching. These first-hand sources can include autobiographies, diaries, letters, speeches, and poems. Primary biographical sources can also include audio recordings, film recordings, or transcripts of interviews in which the person you are researching is the interviewee.

- Secondary biographical sources are sources written by someone other than the person you are researching. Secondary sources provide second-hand accounts that analyze, interpret, or comment on a person’s life.

There are three ways to start searching for biographical information:

- Look for articles in full-text databases, such as authors in Literary Reference Center and Literature Resource Center (Gale) or other persons in Biographies (Encyclopaedia Britannica).

- The library usually has many biographical sources. Check a general or specialized encyclopedia for a brief summary of the person’s life.

- Do a subject search in the library catalog to find books written by or about a specific person.

Critical Reviews

A review is a critical evaluation. By reading reviews, you can determine the quality of a book or a movie.

Book Reviews

Books are reviewed in newspapers, magazines, and scholarly journals. Ordinarily a book will be reviewed within a year after it is published, although it may be reviewed later.These two library databases are helpful for finding book reviews:

- Academic Search Complete has references to reviews and in some cases the full text. In the advanced search, under “Limit Your Results,” use the drop-down box for “Document Type” and select “Book Review.” Enter the title in the search box.

- Literature Resource Center (Gale) allows you to search specifically for book reviews from magazines and journals. Click on “Advanced Search” and in the “limit by content type” box, select “Reviews and News”.

Search Tip: Not all databases that contain book reviews have a search limiter for book reviews. In this case, it may be useful to use a truncated word search. For example, these searches will find results with both review and reviews.

- (three blind mice AND review*)

- (three blind mice AND book review*)

- See Lesson 3: Searching Library Databases for more information on truncation.

Movie Reviews

Like books, movies are reviewed in magazines and newspapers. Movies are also reviewed on a variety of Web sites.

These two databases are helpful for locating movie reviews:

- Academic Search Complete also has references to movie reviews. In the advanced search, under “Limit Your Results,” use the drop-down box for “Document Type” and select “Entertainment Review.” Enter the movie title in the search box.

- Internet Movie Database (IMDb) has reviews from newspapers, film magazines, and other Web sources.

Government Information

Government information includes any publication issued by local, state, national, or international governments. Government information includes laws, regulations, statistics, consumer information, and much more. Documents cover topics ranging from AIDS to the environment. In fact, it is hard to think of a topic you would not find in government documents. If you are writing a research paper, a search for government information on your topic should be an essential step in your search. If you need help finding government documents on your topic, ask at the reference desk.

Government information is generally considered to be reliable and is available in a wide variety of formats: reference works, books, periodicals, bibliographies, pamphlets, maps, and CD-ROMs. Your library has a collection of government documents that you can check out, just like books. In addition to the documents available from the library, the full text of many federal and state documents is available from official government Web sites, such as USA.gov and FedWorld.ntis.gov.

How to Find Government Information

Some useful ways to find government information in agency publications, legislation, court cases, and hearings are:

The library catalog

Use the name of a country, state, city, or county in an author search.

GPO Access

Search this government Web site for information on your topic. GPO Access allows you to search official information from all three branches of the Federal Government, including Congressional Bills, Congressional Record, U.S. Code, Federal Regulations, Federal Register, the U.S. Budget and more. You may also download the full text of a bill or law.

Legal Collection

Legal Collection is an authoritative source for information on current issues, studies, thoughts, and trends of the legal world. Legal Collection offers full text for more than 250 law journals. This database provides information centered on the discipline of law and legal topics, such as criminal justice, international law, federal law, organized crime, medical, labor & human resource law, ethics, the environment, and much more.

LexisNexis Academic

Use this library database to search for full text of bills, laws, regulations and much more.

The National Archives

This agency’s Web site has a searchable archive of historical documents and materials created by the U.S. government, including the U.S. Constitution, Bill of Rights, and Amendments.

Official Web sites

You can access all official U.S. government agency Web sites and their online publications from USA.gov, the government’s official web portal. Alternately, try these Web search strategies:

- Search for the government agency name and the word “publications,” e.g.: “EPA publications.”

- Search for your subject term and ‘site:.gov,’ e.g.: “water pollution site:.gov”

Statistical Information

Statistics are a valuable kind of information in research because they can provide data for making comparisons and determining historical trends. When you write a paper, give a speech or make a presentation, your argument will in many cases be more convincing if you can use statistics to back up what you say. The U.S. government is one of the largest and most important publishers of statistical information. Many of its agencies and departments have statistical divisions which regularly publish statistical abstracts and digests of basic socio-economic data about the United States.

One of the best sources of statistical information published by the U.S. government is The Statistical Abstract of the United States. Published annually since 1878 by the U.S. Bureau of the Census, the Statistical Abstract presents quantitative summary statistics of the U. S. government as well as some private agencies. It covers social, economic, and political aspects of the country such as population, vital statistics, immigration, education, labor, and transportation. Other government agencies which are good sources of data include

Library databases such as Academic Search Complete, World Data Analyst (Encyclopædia Britannica), and Statistical Abstract of the United States (ProQuest) also provide statistical information. In these databases, you can use “statistics” as one of your search terms, such as “alcoholism and statistics,” to get articles with statistical information in them. Look for search options that allow you to specify statistical information:

- In Academic Search Complete, click on “Advanced Search” and under “Limit Your Results,” check the boxes next to “Image Types – Chart, Diagram and Graph.” Enter your search terms.

- Census Data (U.S. Census Bureau)

- Georgia Census Data